Kind advice: this article is suggested to be read on the web since it is over the limit size of a email and content might get truncated.

Fuji in Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e, also known as “pictures of the floating world”, is a genre of Japanese art that flourished during the Edo period (17th - 19th). Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings to describe the hedonistic lifestyle.

Fuji, one of the many subjects displayed in Ukiyo-e, haunts Edo Japan and especially haunts the floating world.

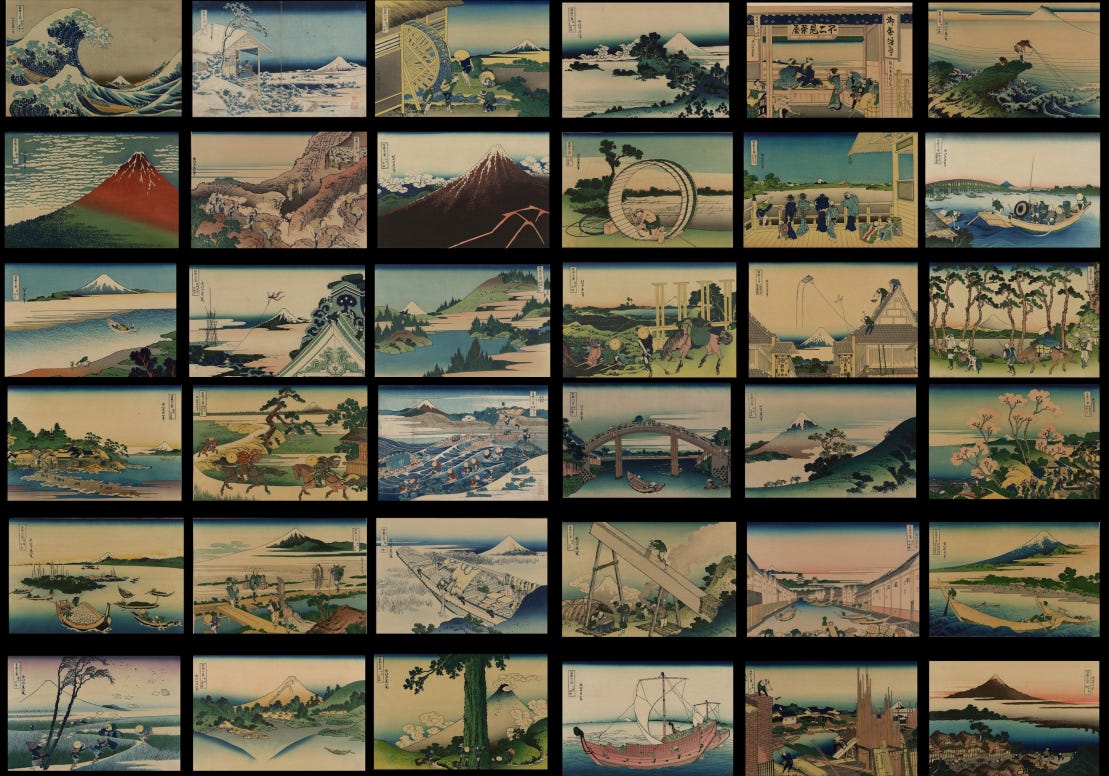

Many people have seen the Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, a series of landscape prints by the Japanese artist Hokusai, which depicts Mount Fuji from different locations and in various seasons and weather conditions. Fuji was seen as the source of the secrets of immortality in Japanese tradition, a powerful recurring theme.

It is a metonym for Japan as a whole.

It is bigger than all of us.

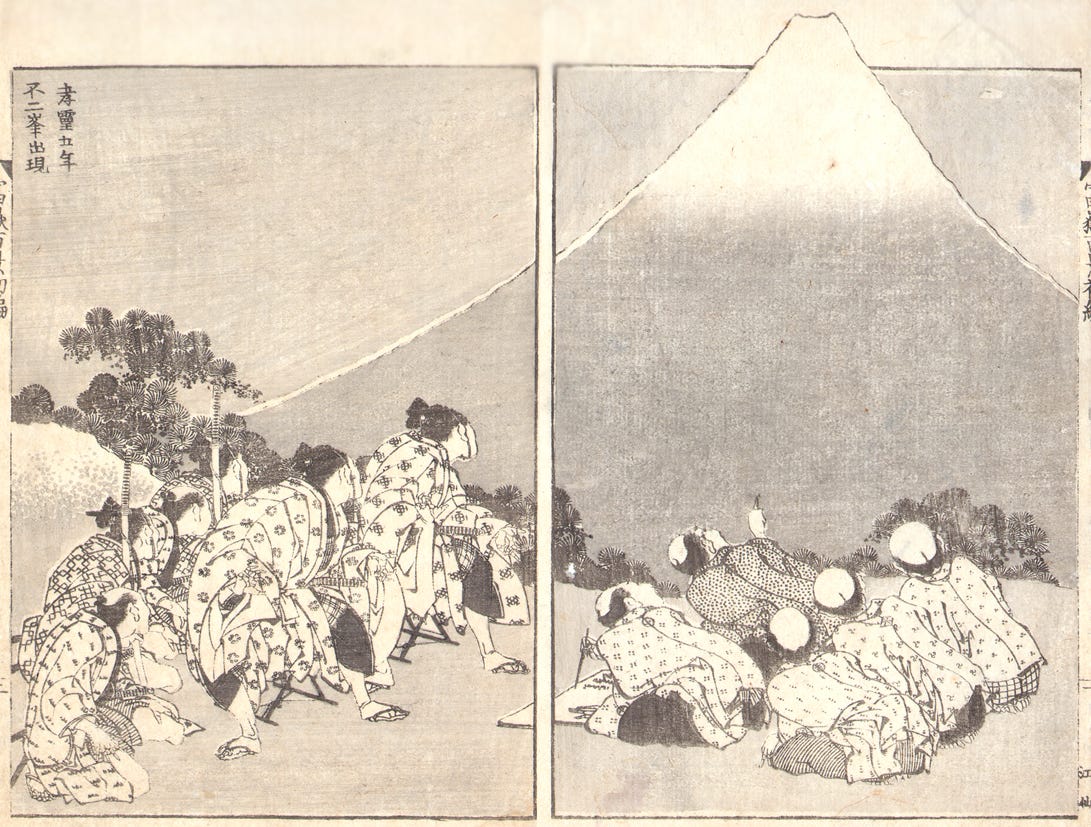

And sometimes, smaller than us.

It is both literal and conceptual, both banal and uncanny.

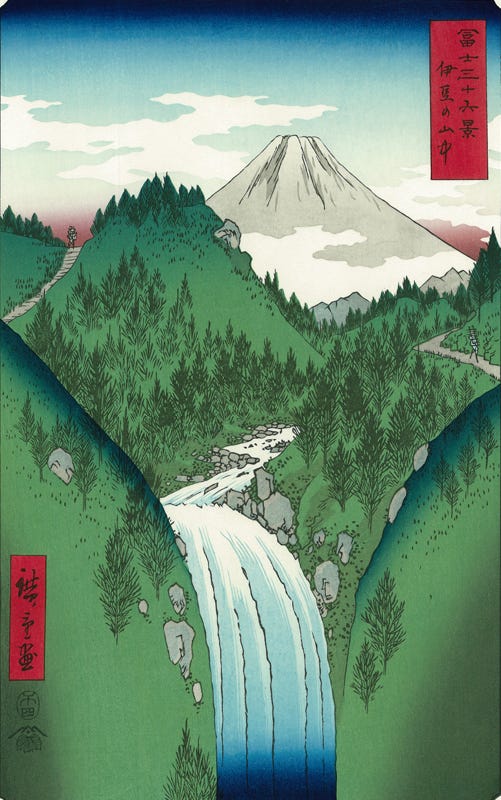

It is sometimes looming

Sometimes distant.

Always and already there.

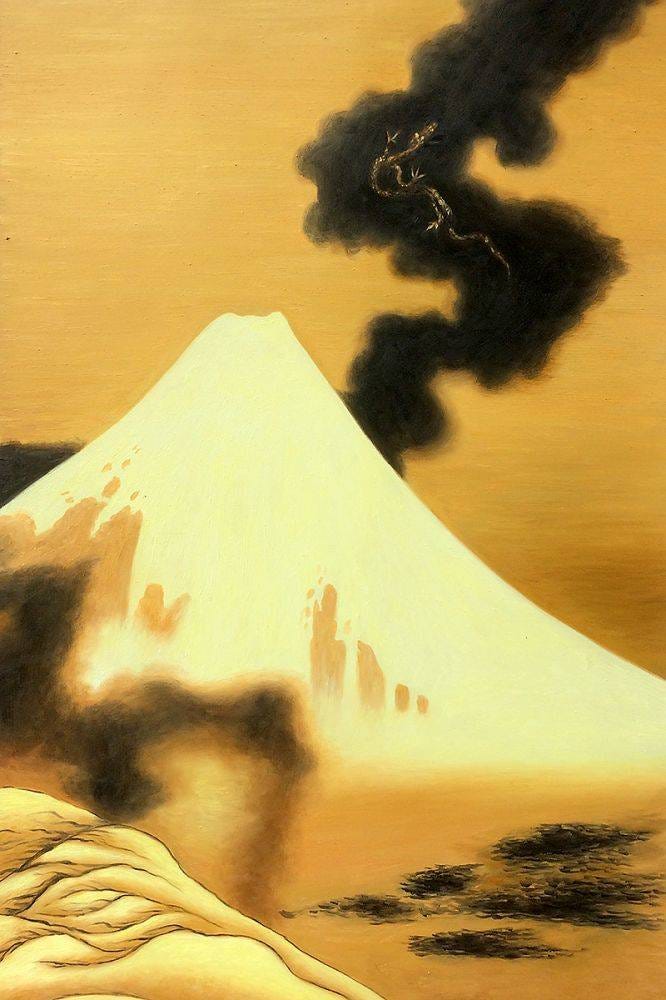

It is a focal point for elaborating and integrating an entire cosmology: on timescales both long…

and short.

It integrates nature, the sacred, the human, the social, the provincial, the technological, and the commonplace.

The Edo Japanese understood it to be lifegiving…

But also a source of precarity.

Even at times an existential threat.

Our Fuji is intelligence

Like the totalization Fuji presents on woodcut, intelligence can be applied to different sorts of systems as a way to understand computers, brains, societies, ecologies, planets, arguably everything and beyond.

To understand this mountain and grapple with the big questions (people, machine, philosophy, ethics, historiography, art and creativity…), we’ll need to take on a lot of perspectives, some with very different timescales, landmarks, and points of references - though they are connected…

In fact, for a long time, we take intelligence as an emotional concept, an unwillingness to admit that mankind can have any rivals in intellectual power. Alan Turing in his unpublished 1948 paper Intelligent Machinery says that “The extent to which we regard something as behaving in an intelligent manner is determined as much by our own state of mind and training as by the properties of the object under consideration.” Also, people view intelligence that’s not derived from humans as a threat. In Turing’s later 1951 paper Can Digital Computers Think, he says “Many people are extremely opposed to the idea of a machine that thinks, but I do believe that it is not for any of the reasons that I have given, or any other rational reasons, but simply because they do not like the idea.” This resistance to non-human intelligence is deeply held but nevertheless erroneous in assumptions regarding individual originality and inventiveness. The opposition is a reflection of anthropocentrism, also known as human exceptionalism, the belief that human beings are the most important entity in the universe.

Besides machine intelligence, we need to consider all kinds of intelligence both collective and computational, in addition to human and individual. Just like in those Ukiyo-e arts,

the mountain is always in view.

Resources:

Alan Turing, Intelligent Machinery, 1948.

Robert Merton, Resistance to the Systematic Study of Multiple Discoveries in Science, 1963

Alan Turing, Can Digital Computer Think?, 1951

Alan Turing, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, 1950

Blaise Aguera y Arcas, Intelligent Machinery, Identity, and Ethics

Hokusai wave = recursive equation

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/natures-beautiful-equation-primer-understanding-kevin-facinelli